Open Source Ecology is an ambitious project to develop self-sufficient human-scale high-tech communities with the basic machinery and tools for production of all, or most of, the goods necessary to live a comfortable life in a small community. Supported by modern technology and working in a globally networked environment, its members shouldn’t have to work too many hours per week. OSE is a case of radically applying the concepts of free knowledge and peer production to the production of most human needs.

In this brief case study, we will explore the foundations and guiding principles of OSE, it’s main project – the Global Village Construction Set (GVCS)-, the team, the business models, their plans and current status, challenges and end with lessons learnt and some conclusions. The information comes mostly from the OSE wiki and blog, several mailing lists and some direct email exchange with several core team members.

Introduction

“Imagine if you could build cars, industrial robots, engines, and other things in your own back yard. The only problem is, these require billions of dollars of infrastructure in the current industrial system. Not for long – if we succeed with the Open Source Micro-Factory.”

In the founder’s words, OSE is a BHAG, a Big-Hairy-Audacious-Goal. And that’s what it is, extremely audacious. It is an attempt to show a radical application of the concepts of “free knowledge”, “commons” and “peer production” in the area of small scale industrial production to build sustainable local economies in collaboration with a global community.

Most machines for that goal have been designed (with their designs and bill-of-materials published) and several already built as prototypes, while at the end of 2011 a crowdfunding campaign at Kickstarter and a few private grants have brought in the needed funds to take into production several other machine prototypes.

At a TED Talk in February 2011, founder/coordinator Marcin Jakubowski explains the main ideas, plans and results by then:

Foundations

At the heart of the project lies a search for freedom and self-sufficiency: “Are you tired of selling your time only to make money for somebody else, leaving only rare moments and weekends to do what you love (if you have any energy left at that point)? What if you could eliminate the bureaucracy in your life? What if you could end your personal financial contribution to war and keep your money out of the coffers of corporate leaders? We are developing the tools, the networks and community to make technologically modern self-sufficient living possible for everyone. Is it time to begin producing only enough to provide yourself a quality life? Are you ready to divorce yourself from systems that require coercion, injustice, and ecological ruin, while fostering a connection to the land and developing your own true talents? This radical move is increasingly within your reach. ”

Their guiding philosophies include a commitment to free software, proposes a cooperative enterprise form that is distributive and designed to be replicable, encouraging autonomy, open development, resilience, local community, and keeps a strict gatekeeping policy for “dedicated project visits” through a serious social contract.

To contribute to a post-scarcity economy, OSE works for replicability, to help other people and groups copy the initiative or parts of it. This obviously requires sharing the specifications and design files, but also comes back in various more high level ideas of industrial production. Flexible fabrication is one such idea, where manufacturing can be quickly adjusted to changing needs: this can be done so by using less specialised machinery with high skilled operators. This fits with the idea of “Small is Beautiful” as opposed to large scale, capital intensive mass production. They combine this idea with a collaboratively-developed, global repository of shared product designs. They see this as “… particularly useful [way] towards relocalization of productive economies and towards distributive economics.”

OSE Mission

“Open Source Ecology (OSE) is a movement dedicated to the collaborative development of tools that enable open access to the best practices of economic production – to promote harmony between humans and their natural life support systems, and to remove material scarcity from determining the course of human relations, globally and locally. OSE aims to create harmonious coexistence between natural and human ecosystems (if we assume these are separate), towards land stewardship, resilience, and improvement of the human condition. OSE is pursuing the creation of an open society, where everybody’s needs are met, and where everybody has access to information, material productivity, and just governance systems – such that human creativity is unleashed, for all peoples. ”

Ecology and design for durability and reuse

Both from an ecological and economic perspective, there are many interesting elements in the OSE philosophy. First they intent to design from a systems perspective, not just for isolated aspects. This includes Design-for-Disassembly; Design-for-Scalability. Second, products are designed for lifetime duration, instead of current design for obsolence. That reduces depreciation, and thus the work needed to sustain oneself. Third, products are designed based on a modular approach, which simplifies the design and manufacturing while also reducing the number of different versions for a specific function.

Both from an ecological and economic perspective, there are many interesting elements in the OSE philosophy. First they intent to design from a systems perspective, not just for isolated aspects. This includes Design-for-Disassembly; Design-for-Scalability. Second, products are designed for lifetime duration, instead of current design for obsolence. That reduces depreciation, and thus the work needed to sustain oneself. Third, products are designed based on a modular approach, which simplifies the design and manufacturing while also reducing the number of different versions for a specific function.

Brief history and first successes

The predecessor project Open Farm Tech, which started in 2003, actively developed various forms of permaculture for ecological food production. They were able to construct the first version of the Compressed Earth Brick Press by 2007 to produce their own bricks for constructing the initial Factor e Farm. When the landlord got wind of this, he cancelled the lease of the land and they were forced to relocate. In 2008 the Factor e Farm was relaunched on a piece of land in rural Missouri.

The movement nevertheless continued building under the name Open Source Ecology and became known to the larger public in early 2011, when founder Marcin was invited to present a TED Talk. Soon after, Make Magazine and other media started to publish about OSE.

In order to generate funds to bring these ideas into reality, a strategy to collect donations has been started. People are asked to make monthly donations of 10 US$ and become a so-called True Fan. The idea is inspired in Kevin Kelly‘s reflections on the Long Tail, where he argues that any artist, author or developer needs to have 1000 True Fans to make a living. By end of 2011 the OSE has reached a level of 450 True Fans who make their monthly contribution.

Currently prototypes have been built for these four machines: the LifeTrac tractor, the automated Compressed Earth Bricks Press, Power Cube and Soil Pulverizer. Furthermore the full blueprints for these four and documentation of the CNC torch table have been made available to the public by Christmas 2011.

The crowdfunding platform Kickstarter was used to start a drive for small contributions aimed at raising US$40.000. The campaign ended in November 2011 and exceeded the goal, raising US$63.573 pledged by 1384 people.

Global Village Construction Set

“The Global Village Construction Set (GVCS) is a modular, DIY, low-cost, high-performance platform that allows for the easy fabrication of the 50 different industrial machines that it takes to build a small, sustainable civilisation with modern comforts, ” according to the Open Source Ecology website. This is currently the core project where most attention is focused within OSE.

Keyfeatures

It’s keyfeatures:

- Free knowledge and open development – all 3D designs, schematics, instructional videos, budgets, and product manuals are published under free licenses on the Wiki and open collaboration with technical contributors is encouraged.

- Low-Cost – The cost of making or buying GVCS machines are, on average, 8x cheaper than buying from an industrial manufacturer, including an average labour cost per hour for a GVCS fabricator.

- Modular – Motors, parts, assemblies, and power units can be interchanged, where units can be grouped together to diversify the functionality that is achievable from a small set of units.

- User-Serviceable – Design-for-disassembly allows the user to take apart, maintain, and fix tools readily without the need to rely on expensive repairmen.

- DIY – (do-it-yourself) The user gains control of designing, producing, and modifying the GVCS tool set.

- Closed Loop Manufacturing – Metal is an essential component of any advanced civilisation, and the platform allows for recycling metal into virgin feedstock for producing further GVCS technologies – thereby allowing for cradle-to-cradle manufacturing cycles.

- High Performance – Performance standards must match or exceed those of industrial counterparts for the GVCS to be viable.

- Flexible Fabrication – It has been demonstrated that the flexible use of general machinery in appropriate-scale production is a viable alternative to centralised mass production.

- Distributive Economics – the replication of enterprises that derive from the GVCS platform is encouraged as a route to a truly free enterprise.

Cost reduction

Indicative cost comparison between GVCS material costs vs. commercial machines

It must be noted that the OSE designed machines only include materials costs, and exclude the labour to fabricate them. Furthermore, these are estimates, as most machines have not yet been prototyped. Nevertheless, these estimates have some consequences for our ideas about the scale of production. The concept economy of scale indicates that production costs per unit go down if the scale is going up. That’s why in many industries mass production is found to be most competitive. From these estimates however we can infer that even small scale production can be economically viable, or even more attractive.

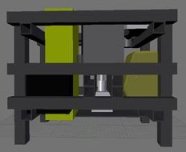

A prototype of the PowerCube

The PowerCube is a modular, universal, self-contained power unit consisting of an engine coupled to a hydraulic pump, providing power from hydraulic fluid at high pressure. It is designed to function as a modular and interchangeable power supply for GVCS technologies, and is the basic building block for a long list of other machines, such as the tractor, truck, car, CNC torch table, iron worker, saw mill, etc.

The PowerCube is a modular, universal, self-contained power unit consisting of an engine coupled to a hydraulic pump, providing power from hydraulic fluid at high pressure. It is designed to function as a modular and interchangeable power supply for GVCS technologies, and is the basic building block for a long list of other machines, such as the tractor, truck, car, CNC torch table, iron worker, saw mill, etc.

The current version of the power cube is based on an off-the-shelf gasoline engine, but the design is intended to be as power source agnostic as possible so that the power production can be readily changed. While now working on gasoline, future versions are expected to work on biofuel and biomass as well. Future variations on the power cube will keep a similar size and outside connections, so as to enable other GVCS machines that use the power cube can easily swap it for another.

The current version of the power cube is based on an off-the-shelf gasoline engine, but the design is intended to be as power source agnostic as possible so that the power production can be readily changed. While now working on gasoline, future versions are expected to work on biofuel and biomass as well. Future variations on the power cube will keep a similar size and outside connections, so as to enable other GVCS machines that use the power cube can easily swap it for another.

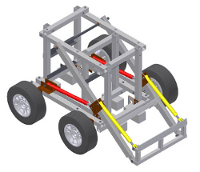

A prototype of the LifeTrac Tractor

The LifeTrac is a low-cost, multipurpose, open hardware tractor. It is modular and consists of a power cube engine – that in itself is also used for building the steam engine, saw mill or other workshop equipment. It can be used in combination with other tools to convert it into e.g. a baler, seeder, compressed earth brick press, soil pulverizer etc.

The LifeTrac is a low-cost, multipurpose, open hardware tractor. It is modular and consists of a power cube engine – that in itself is also used for building the steam engine, saw mill or other workshop equipment. It can be used in combination with other tools to convert it into e.g. a baler, seeder, compressed earth brick press, soil pulverizer etc.

Just before Christmas 2011 the OSE team has published a first instruction video of how this tractor is built. A more complete set of information is promised in the forthcoming “Civilization Starter Kit DVD”. See also the Make guide.

Just before Christmas 2011 the OSE team has published a first instruction video of how this tractor is built. A more complete set of information is promised in the forthcoming “Civilization Starter Kit DVD”. See also the Make guide.

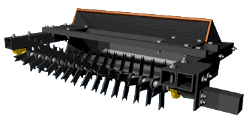

A prototype of the SoilPulverizer

The Soil Pulveriser is an extension to the tractor that tills soil with blades via rotary action. It is designed to stir and pulverise the soil, either before planting (to aerate the soil and prepare a smooth, loose seedbed) or after the crop has begun growing to kill weeds (controlled disturbance of the topsoil close to the crop plants kills the surrounding weeds by uprooting them, burying their leaves to disrupt their photosynthesis, or a combination of both). Soil Pulverisers are designed to disturb the soil in careful patterns, sparing the crop plants but disrupting the weeds.

The Soil Pulveriser is an extension to the tractor that tills soil with blades via rotary action. It is designed to stir and pulverise the soil, either before planting (to aerate the soil and prepare a smooth, loose seedbed) or after the crop has begun growing to kill weeds (controlled disturbance of the topsoil close to the crop plants kills the surrounding weeds by uprooting them, burying their leaves to disrupt their photosynthesis, or a combination of both). Soil Pulverisers are designed to disturb the soil in careful patterns, sparing the crop plants but disrupting the weeds.

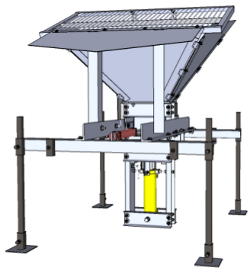

A prototype of the Compressed Earth Brick Press

The “Liberator” Compressed Earth Bricks Press, or CEB Press is a machine that makes compressed earth blocks (see OSE Wiki, or the Make guide). The CEB Press takes earth/dirt/soil and compresses it tightly to make solid blocks useful for building. It is an automated press that can produce 16 bricks per minute, which is several times higher than comparable machines from the industry, though it costs just about 4.000 US$ in material costs instead of a ten times higher price to buy a commercial product.

The “Liberator” Compressed Earth Bricks Press, or CEB Press is a machine that makes compressed earth blocks (see OSE Wiki, or the Make guide). The CEB Press takes earth/dirt/soil and compresses it tightly to make solid blocks useful for building. It is an automated press that can produce 16 bricks per minute, which is several times higher than comparable machines from the industry, though it costs just about 4.000 US$ in material costs instead of a ten times higher price to buy a commercial product.

The Liberator is designed to be attached to an external power source, such as the LifeTrac tractor or a PowerCube. It needs as little as one person to operate. Using the CEB Press, two people can build a 6 foot high (1.83m) round wall, 20 feet (6.1m) in diameter, 1 foot (30cm) thick, in one 8 hour day.

The Liberator is designed to be attached to an external power source, such as the LifeTrac tractor or a PowerCube. It needs as little as one person to operate. Using the CEB Press, two people can build a 6 foot high (1.83m) round wall, 20 feet (6.1m) in diameter, 1 foot (30cm) thick, in one 8 hour day.

The remainder of the 50 GVCS tools

With the first 4 tools prototyped, there are 14 more to go to build the basic package that is needed to build the other 32. The complete GVCS is comprised of the following tools: ![]() 3D Printer,

3D Printer,![]() 3D Scanner,

3D Scanner,![]() Aluminum Extractor,

Aluminum Extractor, ![]() Backhoe,

Backhoe,![]() Bakery Oven,

Bakery Oven,![]() Baler,

Baler,![]() Bioplastic Extruder,

Bioplastic Extruder,![]() Bulldozer,

Bulldozer,![]() Car,

Car,![]() CEB Press,

CEB Press,![]() Cement Mixer,

Cement Mixer,![]() Chipper Hammermill,

Chipper Hammermill,![]() CNC Circuit Mill,

CNC Circuit Mill,![]() CNC Torch Table,

CNC Torch Table,![]() Dairy Milker,

Dairy Milker,![]() Drill Press,

Drill Press,![]() Electric Motor Generator,

Electric Motor Generator,![]() Gasifier Burner,

Gasifier Burner,![]() Hay Cutter,

Hay Cutter,![]() Hay Rake,

Hay Rake,![]() Hydraulic Motor,

Hydraulic Motor,![]() Induction Furnace,

Induction Furnace,![]() Industrial Robot,

Industrial Robot,![]() Ironworker,

Ironworker,![]() Laser Cutter,

Laser Cutter,![]() Metal Roller,

Metal Roller,![]() Microcombine,

Microcombine,![]() Microtractor,

Microtractor,![]() Multimachine,

Multimachine,![]() Nickel-Iron Battery,

Nickel-Iron Battery,![]() Pelletizer,

Pelletizer,![]() Plasma Cutter,

Plasma Cutter,![]() Power Cube,

Power Cube,![]() Press Forge,

Press Forge,![]() Rod and Wire Mill,

Rod and Wire Mill, ![]() Rototiller,

Rototiller,![]() Sawmill,

Sawmill,![]() Seeder,

Seeder,![]() Solar Concentrator,

Solar Concentrator,![]() Spader,

Spader,![]() Steam Engine,

Steam Engine,![]() Steam Generator,

Steam Generator,![]() Tractor,

Tractor,![]() Trencher,

Trencher,![]() Truck,

Truck,![]() Universal Power Supply,

Universal Power Supply,![]() Universal Rotor,

Universal Rotor,![]() Welder,

Welder,![]() Well-Drilling Rig,

Well-Drilling Rig,![]() Wind Turbine.

Wind Turbine.

Localisation levels: step-by-step substitution

As these ambitious goals cannot be realised all at once, a strategy to bootstrap or kickstart the process is followed. The GVCS tools will be built in three general stages: first, machines are built by using Commercial Of The Shelf (COTS) parts; second, they’re built based on parts fabricated by OSE using available materials; third, machines are built from parts fabricated from materials produced in OSE factors. So everytime a new machine is ready, that can be used to produce the parts necessary for other machines and thus substitutes the need to buy parts from commercial manufacturers. The maximum level of localisation will be reached when also the primary resources necessary for the production process are locally extracted from local materials, like scrap metal, bioplastics or clay.

Localisation applies to the creation of natural economies, or those economies based on the substance of their own, natural resources, free of supply chain disruptions. An example of level 3 is the aluminium extractor where local aluminium is made by smelting aluminium from local clays.

The team

The Open Source Ecology movement was initiated by Marcin Jakubowski. Marcin is a Polish American with a bachelor in chemistry from Princeton and a PhD in physics from the University of Wisconsin. He defines himself as a self-made industrial designer and guides the development of all GVCS tools as the director of OSE and of FeF.

As the movement takes place at a global scale, connected through the net, lots of people contribute from a distance. They designed a way to encourage a team culture and ask people to join by filling out a survey to explain who they are, what motivations they have and what they could contribute. A few hundred people have been recorded through this survey. It remains however unclear how many of these people are actively involved – but it seems to have helped finding subject matter experts for several areas.

Current core team members include Isaiah Saxon (Media Director), Adrian Hong (Advisor), Luis Diaz (Business Consultant), and Elifarley Cruz (Web Administrator). Let us highlight a few of the active people to get a feel for the composition of the team.

Elifarley Cruz is a Brazilian Free Knowledge advocate, Free Software developer and contributor to the P2P Foundation. Elifarley is administrator of the web infrastructure for the OSE community.

Nikolay Georgiev has been working as a software developer. Being born in Bulgaria, he relocated to Germany. Nikolay is in OSEs IT team, works as facilitator in the OSE community and develops proposals for microfunding strategies. Besides, he is helping with organisation and communication in Europe to set up Open Source Ecology Europe and tries to get a FeF started in Germany.

Mark J Norton is a senior software architect, developer and e-learning systems expert who runs his own consultancy company in the US. He joined OSE in April 2011. One of his motivations is to have the tools needed to create a self-sufficient life on his farm. He is involved in the LifeTrac and is project leader of the modern steam engine. Besides, he is a True Fan and wiki curator.

Brianna Kufa is probably the single, most active woman in OSE at this time. She did a dedicated project visit last year (see her log). She is currently working on the Ironworker Machine. Her family has a background in machine shop work and she grew up in that environment. She was a competent machinist before getting involved in OSE. She plans to fabricate GVCS machines for business purposes in the LA area.

Yoonseo Kang is a Canadian who’s living on site. He’s in charge of the CNC Circuit Mill and the Inverter component of the Universal Power Supply.

Mike Apostol, also from Canada, is in charge of the CAD / CAM design of the various tools. He is currently living on-site and helps other people to use FreeCAD or other Free Software design solutions.

Apart from Brianna (and Rebecca Rojer) there don’t seem to be many women involved. This might be a general issue in more technical environments and can be seen in ICT communities at large. Maybe some work could be done to improve the gender balance, as experience and research shows that communities can be generally more effective when men and women work together.

As the real work takes place at the FeF – being the primary R&D site within OSE – motivated people are invited to come for a so called “Dedicated Project Visit”. People visit the FeF site usually from one to three months and aim to work on those tasks they are good at and that are in need. This method works as a way to spread the understanding of the GVCS and FeF to help other groups set up their local versions.

The people living and working on-site rotate a lot, and it is therefore not very clear who actually lives there at this moment; right now that could be 6-7 people.

Economic Aspects

On the one hand, there are the macro aspects of “distributive economics” and open business models and on the other, the concrete financial expectations at the Factor e Farm.

Let’s first review “distributive economics”; what does that mean? According to the OSE wiki: “Distributive Economics is an economic paradigm which promotes the equitable distribution of wealth through a combination of: open design (of products, processes, services, and other economically significant information), Flexible Fabrication, and Open Business Models towards replicability. This means that replication is promoted to as many economic players as possible. Here at OSE, an apolitical approach is taken where design is improved by local solutions without invoking the context of centralized power. ”

The idea is that everyone individually or in a group can get access to the machines needed to sustain themselves. While currently gaining access to (and control over) industrial production facilities requires serious capital expenditure, the proposed model works based on free knowledge and peer production. By avoiding patents and restrictive copyright policies and instead sharing designs and manufacturing information through online communities and repositories, far less costs are incurred, while innovation can in principle occur much faster. Instead of reinventing the wheel (or machine or product), global collaboration helps people to be more efficient. This has been shown in the Free Software community and OSE tries to show this for physical machines and products. Their approach is pragmatic and results driven, while working according to their set of founding principles (value driven). Where most open business models focus only on having open access to the product design, OSE’s open business model goes much further, as also the means of production are under free licenses and the business organisation as well.

Of course there are lots of hurdles on the road to distributive economics, such as the initial capital investments needed for developing working prototypes, primary resources, finding skilled specialists, … While much lower than market prices for conventional commercial machines, there is still investment needed. The idea is to stay away from loans that need to be paid back with high interest rates and thus force a more traditional business model. Therefore the approach taken by OSE is that of crowdfunding the development of prototypes of the machinery. At the same time, OSE is “building on the ‘knowledge of giants’ applied in a modern way”, according to team member Nikolay Giorgiev, referring to the many other open hardware development communities who share their work under free licenses and enable projects like OSE to reuse that knowledge. In terms of primary resources, an ecological approach is taken to recycle scrap metal and work with materials that are locally available. In terms of skilled specialists, the project has been able to attract people from many places to work together on a global scale. Given that current capitalist industrial production doesn’t offer very positive perspectives for increasing parts of the population, more and more skilled individuals get involved in the movement. This is also partly due to the “open business model”, where people are encouraged to replicate the experience and set up their local Factor e Farm and start making a living off that.

How are the financial perspectives for OSE for the short term? There are several streams of income that are used to continue the development and prototyping of the remaining GVCS tools.

- Current income from True Fans is about 4.500$/month.

- From the manufacturing and sales of products some 6.000$/month came in in 2011. This figure is expected to rise when more machines become productive.

- The crowdfunding campaign at kickstarter brought in some 67.000 US$.

- OSE is shortlisted to get funding from the Shuttleworth Foundation.

- In order to train and help others to replicate the GVCS tools, one can take a six months immersion training at FeF. This is also referred to as the OSE Fellowship Programme. The trainee or fellow is expected to get hands-on experience with the various tools and manufacture products that can be sold on the market. The net earnings for the trainee are estimated to be at 30.000 US$ of which one third is to be paid as training costs to the project.

The project calculates it needs 5,5 million US$ to build and document all 50 GVCS tools. Help is needed to get to this figure. Don’t forget to become a True Fan or make a donation yourself.

To find out about the economy at the Factor e Farm itself, I asked the OSE team. People living at or visiting the farm for now only need to pay for food, while housing and materials are catered for by the project. The project as such is owned by the founder, Marcin, while the Terra Foundation functions as fiscal sponsor to channel donations. People participating in the project can do that at a volunteer basis or get paid for it, depending on personal needs and project needs (sometimes vacancies are announced).

Replication

One of the foundational aspects of OSE is its focus on replicability. The habit to help participants in the community at large has shown most effective in online communities from various types. The general idea is that participants in the community share the improvements they make – at least in digital form – so each benefits from the collective work. The idea of sharing and enabling each other comes back in many aspects in OSE.

First, the main ideas and knowledge are shared through various online tools of which the wiki is most prominent. They say: “If it isn’t in the wiki, then it doesn’t exist” to encourage people to document anything relevant on the wiki. This is also seen as a way to gain reputation in the community.

Second, all explicit knowledge is considered free knowledge and is licensed under free licenses. This applies to blueprints, CAD and CAM design files, bills of materials, test data, documentation, manuals, instruction videos etc. That’s why we can consider this really Free Hardware: anyone has the four freedoms to reuse and replicate as he or she sees fit. A strong example is the so called “Civilization Starter Kit“, a DVD with all information needed to build the first working machines ready for replication.

Third, the old educational model of mentor-apprentice is used. The experienced makers supervise newcomers when they try to replicate an existing tool. This can be observed e.g. in the Replication page.

Fourth, they promote the idea of a “distributive enterprise”, which they define as: an enterprise which maintains the replication of such an enterprise by others at the core of its operational strategy. That is what others call the right to fork or branch out (in the software domain). Interested people are invited to become an OSE Fellow. Fellows should, with the proper training, be able to replicate the FeF and run their own “distributed enterprises”.

Fifth, local OSE groups have been started up to follow the example of the first FeF in various places. Recently a chartered programme has been suggested, where local groups can become an official charter. Local charters commit to share a part of their income with the primary farm to invest in R&D which benefits the whole community. Local groups that prefer to be independent are encouraged to list themselves as independent OSE efforts.

Besides that, regional networks are forming, most notably in Europe. Under the working title of Open Source Ecology Europe an initial group of around 160 people has joined so far. While much of the groundwork for such sister initiatives can be reused from the main OSE project, still consensus is needed between the participants on the specific goals and methods, strategies to raise funds and decision-making processes to decide about what to do with them. Interestingly, several local initiatives for buying land and setting up local GVCS facilities are being discussed. The early participants have done field visits to several locations in Spain, Germany, Italy and elsewhere.

Roadmap

With the current $1/2M of funding the plan is to begin rapid parallel development of the GVCS, with the development of 14 further tools in the first months of 2012. From then, the remaining 32 technologies will be developed, building on those first tools, while documenting all results with CAD/CAM design files, howto manuals and instruction videos. When sufficient funding comes in, this will be invested in prototyping, documentation and field testing, and for deploying a fully-featured, open source CAD/CAM solution.

If those machines are prototyped, tested and stable working versions are deployed, then a real Microfactory can be set up. This can be seen as a flexible manufacturing cell, where skilled human operators can produce efficiently the many products that are needed for modern comforts. In short, the Open Source Microfactory is a robust, closed-loop manufacturing system for many kinds of mechanical and electronic devices. It includes the ability to provide its own fuel, electricity, and mechanical power.

If those machines are prototyped, tested and stable working versions are deployed, then a real Microfactory can be set up. This can be seen as a flexible manufacturing cell, where skilled human operators can produce efficiently the many products that are needed for modern comforts. In short, the Open Source Microfactory is a robust, closed-loop manufacturing system for many kinds of mechanical and electronic devices. It includes the ability to provide its own fuel, electricity, and mechanical power.

Comparison to other communities

As OSE builds on top of many other successful ideas and communities, it may be good to pause for a moment and see how they relate.

Free Software communities: OSE has got much of its inspiration from the 30 year old free software communities, and in fact “open hardware” is directly derived from that, by applying the four freedoms defined by the Free Software Foundation to the sharing of designs, blue prints and documentation. On a more concrete level, OSE also uses all kinds of free software, to run its servers, websites, community and social enterprise systems. And many of the software systems used to run the high-tech machines are free software.

Free/Open Hardware communities: OSE participates in several of the most exciting and successful Free Hardware projects and communities. As OSE tries to advance some of the production machines, it contributes actively. The challenge may be to feed back new experiences obtained in the process back into the original projects. Then again, the OSE team shows a strong emphasis to documenting each step in the process so others can replicate. It can be expected that this leads also back into the original projects.

Maker Culture: people designing, experimenting with and building their own hardware projects are called makers. Maker culture is a subculture of DIY culture applied to hardware. OSE is clearly part of that culture. Besides, it was the Make Magazine that was one of the first to publish about OSE to a large audience.

Ecologic and green movements: the project is based in ecology and sustainability and provides inspiring examples for transitioning towards a sustainable ecology.

Transition Towns / Global Villages movement: The Transition network supports community-led responses to climate change and shrinking supplies of cheap energy. Related to that, Global Villages are defined as:

“A Global Village is simply and basically the synergetic relationship between a local learning center with access to global knowledge (Telecenter, Hub, Library, …) on one side with a local living environment in which this knowledge can be applied, tested, enhanced on the other side. Together they form a local habitat with a global support system.

A Global Village needs to be resourceful in access to the world of information and culture, as well as it needs to be resourceful in access to local resources, material – energetical cycles, inhabitants, processes, biotopes etc. The purpose of a Global Village is to provide a high quality, healthy, satisfactory, secure and sustainable lifestyle to its inhabitants and improve and densify the local life process.”

While the term Global Village was first coined by Marshall McLuhan, it seems that the choice for the name “Global Village Construction Set” is derived from the Global Villages, as defined above.

Cooperatives and social economy: first of all the effort of developing the GVCS is a global cooperative effort, where all participants are co-owners, not of the actual physical machines, but of the designs and knowledge that goes into building them. The “distributive economics” and “distributive enterprise” for setting up local Factor e Farms can be seen as an inspiring form of “social economy”. And to prove this, it can be inferred from the enthusiasm in local cooperative movements that have found out about OSE and are considering its adoption.

Commons: the commons can be defined as goods, be it tangible or intangible, natural resources or social spaces which are jointly developed and maintained by a community and shared according to community-defined rules. The commons is suggested as an alternative to the dichotomy of state-controlled versus mercantile ownership. How does the paradigm of the commons apply to OSE? It does in several ways as we can see. First, the open access and free licensing of the knowledge in OSE make it a knowledge commons. Second the participatory nature and peer production are typical characteristics of a commons. Third, the vision to enable communities to become self-sustainable is in itself a core aspect of any commons-based project.

Cooperation and development: Many Western countries’ policies for foreign aid and cooperation NGO’s include in their goals to help low income countries to become economically independent. While the GVCS and OSE are designed for any community, be it in the North or in the South, it can be expected that the ideas proposed by OSE can be rather inspiring and useful for cooperation and development initiatives.

Lessons and challenges

In this brief case study we have learnt various lessons and identified several challenges for the project.

- We learnt Open Source Ecology’s radical but coherent proposal to develop our own means of production to cater for most of the modern comforts.

- OSE shows that the ideas of Free Software, Free Knowledge and peer production can be effectively applied to hardware production.

- It is to be noted that a Licensing Policy is still under development. All materials on the wiki are dual licensed under both the GNU Free Documentation License 1.2 and the Creative Commons Attribute ShareAlike 3.0. But then at some places they refer to the OSE License which states to use the Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0). This contradictory situation could leave the legal conditions for replication and reuse in a somewhat weak position. It would be good to see this clarified in a coherent Licensing Policy.

- We learnt the difficulties of physical in comparison with intangible goods:

- physical goods are scarce by definition, while intangible goods like knowledge and digital artefacts are abundant;

- the development of the machines require more capital investments than for most digital goods. Nevertheless, the True Fans scheme and crowdfunding experiences show the potential to achieve these goals. For bootstrapping the process, additional grants from private and public sources seem to be necessary.

- while participation can and does happen in some extent through online channels, the physical nature requires people to be on-site to build, experiment and learn. The Dedicated Project Visits are a way to do real work and learn on-site. Then again, there are only few people steady living on the FeF site, which may difficult practical hands-on knowledge transfer. Besides, not everyone can go to Missouri to spend time. Once more local sites become active in the network, participation can be enhanced and the knowledge might spread easier.

- We saw how you can build your own tools (or order them) that are several factors cheaper than commercial industrial versions. They are sometimes even more productive and in all cases designed for long-time durability, modularity and repair.

- We saw how a strategy of modular design can help bootstrap the process of getting to the goal of building the 50 GVCS tools. The first tools are a prerequisite for building the other ones, so a step-by-step substitution of commercial tools can be made. Once the primary resources can also be extracted or produced locally, the community would become fully self-sustainable.

- It should be noted that the obtainment of primary resources is location dependent and for most locations some degree of exchange with the market or other communities will be required.

- Instead of depending on patents and venture capital, the core ingredients for building a self-sustainable community are free licenses, open development and crowdfunding. This takes away the interests on loans as cost component and likewise for patent and copyright rents. Both can take up a considerable part of the costs of industrial products and their absence is considered one of the main reasons for seriously lowering product costs.

- OSE shows how a life out of the consumption society and towards a socially just and ecologically sustainable one can be made possible.

- The aim for self-sustainability is not to be confused with isolated hippy communities from the 1960s and 70s. The ideas of OSE build upon the Global Villages idea of forming a local habitat with a global support system.

- While the community spirit is maximum in almost all aspects of OSE’s work, the ownership of the Factor e Farm is reportedly solely in the hands of the founder, Marcin. This should not necessarily be a problem, but for the effectiveness of the community a more cooperative set-up might seem logical.

- We also learnt that almost all active members in the community are male. While the focus is clearly on getting the job done, some attention to correct the gender imbalance might pay off with a stronger community. The vision for a self-sustaining community would for obvious reasons be most successful in the long run if both men and women participate.

Conclusions

When the machines become replicable and accessible as proposed by OSE, the manufacturing of products can become a service. Local communities with various low-cost machines and capabilities can produce on order and exchange with each other.

As Kevin Carson points out in his book the Homebrew Industrial Revolution, the costs for many products we find on the market nowadays are inflated. Carson sees various trends towards a new, sustainable economy. First, he refers to peakoil and the end of cheap oil, which inevitably will make transportation costs go up and will form an incentive to re-localise certain forms of production. Second, the model of mass production is under pressure due to its various inefficiencies (large capital investments, push instead of pull, large marketing costs and large overhead). While for certain standardised products mass production will remain the most cost-effective solution, new opportunities are emerging for small-scale local production. This is especially true if design and manufacturing information are shared through global networks – as shown by OSE.

Like Carson and others point out, “intellectual property” is what keeps the markets under control, especially by the larger corporations. This not only leads to various inefficiencies but certainly increases the costs of the products, while not delivering on the demands for product design for lifetime duration, repairability, cradle-to-cradle and modularity (as that would go against the aim for profit and market control). OSE in this sense provides a very pragmatic proof of concept to show that a community of skilled and motivated people is very well capable of designing efficient machines, prototype and document them, without relying on artificial legal tools like patents and copyrights.

While OSE defines itself as an “apolitical” movement, its vision fits well with various political and social movements. Much interest can be expected from movements such as ecologists, cooperativists, commoners, left-wing libertarians, freed market thinkers and anti-capitalists.

OSE brings together various social movements, such as the Free Software, Free Culture, Global Villages, P2P and the commons movement. It builds upon their results and tries to give back.

There are many challenges ahead for OSE to break through. Enough donations and income need to be generated to develop the remaining GVCS tools. For that purpose the community strategy and expansion of the network of local charters and facilities is crucial. In order to be most effective organisationally, aspects like the gender inbalance, the decisionmaking processes and ownership issues might need special attention.

The liberating potential of the OSE movement becomes clear. They present a vision for what I’d call a Free Knowledge Society. A society where knowledge is the primary production resource and ICTs are used to create, share and use knowledge for the prosperity and well-being of its people. In such society a mix of various models can live together and operate in the best interest of its participants. OSE presents a very inspiring and promising vision for that. Let us hope OSE continues the success and delivers on its ambitious mission!

A very nice overview of OSE. Covers a lot of what we are trying to do as well as describing the challenges we face.

Posted by Mark Norton | 17/01/2012, 14:58Thank you for your insightful research. I really appreciated reading it.

Posted by Finn | 20/06/2012, 09:46